Thoughts on lawyers, judges, and timing

Let me start with this: I am not a lawyer. That probably bears repeating a half dozen times throughout what I'm about to write, so scroll up every few seconds to re-read this. If you want a lawyer’s take on the Matt Mullenweg & WP Engine saga, I recommend heading over to the excellent WP and Legal Stuff blog from Richard Best.

So, IANAL. Remember it.

With that said... as an outside observer who occasionally follows cases, I have some thoughts on various legal bits and bobs. None of my thoughts are necessarily material to the outcome of the legal fight, but are things I find notable or interesting.

Trademark infringement timeline

In an effort to clear up the timeline that led to Mullenweg calling out WP Engine public at WCUS 2024, Mullenweg joined a livestream with Theo (t3.gg) and opened his calendar and started reading through every meeting he had with Heather Brunner (WP Engine’s CEO) starting in 2018 through to his appearance on stage at WCUS 2024. The implication was that each and every meeting between the two was regarding the trademark issues—that Automattic has been pushing WP Engine for over six years to update its trademark usage and/or pay for a licence. While I think it’s more plausible that Mullenweg met with WP Engine regularly because they are pivotal to the overall WordPress ecosystem, as one of the major managed hosting platforms, these comments mirror the conversation he had with a separate livestream with Prime, mentioning at ~3:15 in:

This is going back years.

And later adding (at ~4:40 in):

Well they tried to delay, delay, which they had been doing for now, 18 months, basically.

... before referencing “years” again, a minute later in the conversation.

I find it inconceivable that Automattic has been discussing this issue with WP Engine for “years,” and certainly not going back to 2018. Why? For starters, if a trademark issue this severe—according to the cease and desist from Automattic—had been occurring for over six years, Automattic’s lack of action would certainly be seen unfavourably by a court. Trademark owners have a responsibility to protect their trademarks from infringement, and a six year period of ignorance, resulting in a reactionary cease and desist does not feel like protection.

Mullenweg has noted repeatedly that he was trusting WP Engine, in good faith—but this argument will not work in a court of law, especially when considering the statute of limitations for such legal action. While there is no federal statute of limitations in the US, in California—where this case was filed and where Automattic is based—trademark infringement falls under the state’s Unfair Competition Law, which has a statute of limitations of four years from discovery of the violating actions.

The UCL requires that lawsuits be brought within four years after the cause of action accrued. The UCL postpones accrual of the cause of action until the plaintiff “discovers” the problem.

If these actions were known in 2018, but not filed until sometime in 2024, I suspect a court will rule that Automattic has missed their window.

(Perhaps a technicality, but Automattic has not filed a countersuit, as of this writing. While a cease and desist was issued against WP Engine, Automattic has yet to file its counter claims in the lawsuit that WP Engine filed.)

About Quinn Emanuel

On September 23, when the original WP Engine cease and desist was first made public, I made the following private remark after seeing the first page:

Not for nothing, but Quinn Emanuel (WP Engine’s attorney in that cease and desist) is no joke. And, they are trial lawyers.

That about sums up my feelings, but I’ll expand a bit...

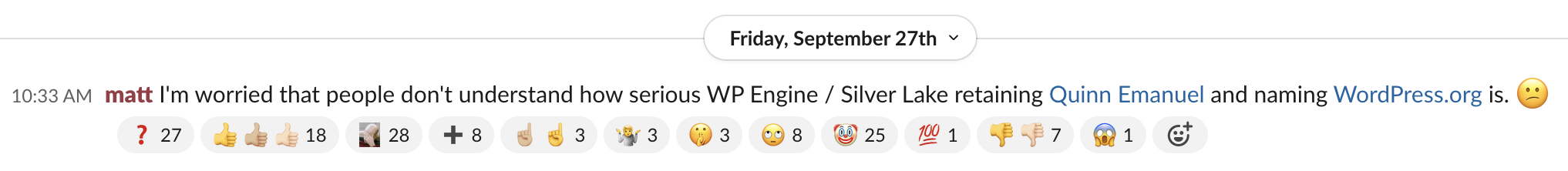

On September 27, Mullenweg posted the following comment in the Making WordPress Slack:

I’m worried that people don’t understand how serious WP Engine / Silver Lake retaining Quinn Emanuel and naming WordPress.org is.

Luckily for the handful of people who are reading this post, over the years, I’ve followed a couple dozen cases in which Quinn Emanuel was an attorney of record. For those of you who do not enjoy reading legal filings and analysis, I’d like to provide a summary of my personal feelings about their work, based on court filings I’ve read, and analysis I’ve seen from lawyers over the years.

To start, Quinn Emanuel focuses on disputes and litigation. They do not focus on being an “outside counsel” to companies, nor providing run-of-the-mill legal services. Instead, Quinn Emanuel is who you call when you know you’re going to court… and you want to win. You may win in arbitration, or at trial, but the vast majority of the time, if you work with Quinn Emanuel, you will win.

In turn, Quinn Emanuel is considered by many to be ruthless. They will act in their client’s best interest at all times and, according to their self-published stats, have been able to win 86% of the time. A recent feature in Bloomberg had the following nugget, in regards to a lawsuit Quinn Emanuel is bringing on behalf of OpenAI:

Again and again in our conversations, [Ravine] returns to that phrase: “the most feared law firm in the world.” Finally, I ask him how he knows this. He turns his laptop toward me and pulls up the email. The signature reads “Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan LLP: Most Feared Law Firm in the World.”

You can imagine then, that clients love Quinn Emanuel. So, who are those clients? Outside of conflicts of interests—and, again, from an outsider’s point of view—Quinn Emanuel seems to represent virtually anyone. Some of their known clients include Bain Capital, Citadel, Elon Musk, Public Investment Fund of Saudi Arabia, and Tesla. Yes, I’m picking and choosing here—they’ve represented GM and Google as well–but I think their ability to represent “anyone” is an important aspect of their firm.

Quinn Emanuel is also known for considering more than “just” the court. As an outside observer to the legal industry, and not at all a lawyer, I personally appreciate their well-written complaints and legal briefs. The WP Engine complaint is a perfect example of this. It’s incredibly readable for just about anyone, avoiding legal jargon unless necessary, devoid of typos, and outlining the specifics not only for a judge, but for anyone interested. Going back to their specialization and clients, Quinn Emanuel is aware that their complaints will be read by reporters around the world—they must be well-written to attract the kind of PR needed to win in the court of public opinion.

For a legal perspective on Quinn Emanuel, that’s primarily focused on the WP Engine complaint, I’d recommend you watch this Twitch stream from Mike Dunford (QuestAuthority). On the quality and thoroughness alone, he calls the complaint is “a six figure” one.

Back to Mullenweg’s comment about “people” not understanding the import of Quinn Emanuel. Given what’s been recently revealed by TechCrunch, Automattic should have been prepared to go head-to-head with law firms like Quinn Emanuel. In stating that they would use legal action from “nice and not nice lawyers and trademark enforcers,” I’d argue that Automattic should have hired Quinn Emanuel as their “not nice” representation for these purposes, if they wanted to win.

The lawyers

This week, we finally discovered who the two lead attorneys will be, representing WP Engine and Automattic.

Representing WP Engine, Rachel Herrick Kassabian, a Partner at Quinn Emanuel. Coincidentally, Kassabian once represented Tumblr, in its pre-Automattic days, but has also represented Google, Vimeo, Samsung, and Pinterest, among others, with a heavy focus on companies in the technology and internet ecosystem. Kassabian specializes in a few key areas that will be relevant to this case, notably Internet Litigation and Trademark / Unfair Competition Litigation. While “Internet Litigation” may not be directly applicable to the case itself, unraveling the three-headed WordPress Foundation-Automattic-WordPress.org monster will require well-written explanations.

Representing both Automattic and Matt Mullenweg, Michael McDonald Maddigan, an Office Managing Partner at Hogan Lovells. While Automattic publicized their retention of Neal Katyal, Maddigan will be the lead attorney. Maddigan’s profile doesn’t provide a quick list of clients he’s represented, mentioning only AMD. Luckily for all of my readers, I did some research. The companies he’s represented include: Anthem, Hertz Custom Benefits Program, Blue Cross, Health Net, Concentra Health Services, UnitedHealthCare, Farmers Insurance (now Truck Insurance Exchange), Laboratory Corporation of America, Apex Digital, LG Electronics, Knix Wear, United States Olympic Committee, and U.S. Paralympics. In that list, you might notice a lot of healthcare and insurance companies... me too. Curious, that.

Bringing it back to Katyal, from a quick scan, I found just two cases where Maddigan and Katyal worked together. In the first case[1], they represented tech companies (Facebook and others) fighting against the US government, which was suing for access to a phone discovered in a black Lexus. The more notable case is John Doe I v. Nestle S A—yes, that case—which eventually went all the way to the Supreme Court, where Katyal successfully argued on behalf of Nestlé that Ivorian children lacked standing to sue for the forced labour occurring in Côte d’Ivoire.[2]

One more thought about Katyal: this type of law isn’t really in his wheelhouse. It’s entirely likely that he will provide support to Maddigan in key ways that benefit Automattic, but Katyal is an appellate lawyer—he’s the person you hire when you need to appeal a case, not when you’re making the initial argument. This might not seem important, but it is! It’s important to lay a solid foundation that can be built upon at each appeal, and some lawyers specialize in getting the first case just right.

Okay, okay, two more quick Katyal thoughts (I can’t help myself):

- While I personally have not validated the conclusion, I have no reason to question the legal research that Mike Julian paid for.

- There is a rumour that Katyal attended Burning Man with Mullenweg. Katyal did attend Burning Man in 2023, but I have no idea if he and Mullenweg interacted. It would be an amusing side note though!

The judge(s)

This one is going to be super inside-baseball, but I find it fascinating.

When WP Engine’s complaint was filed with the court, it was automatically assigned to Magistrate Judge Joseph C. Spero, working for the Northern District of California. Unlike “Article III” judges, who are nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate, magistrate judges are judicial officers, appointed by district judges (the Article III kind). For civil cases, magistrate judges can preside over the entire case and trial, with consent of all parties. Otherwise, they assist district judges with their cases, but do not preside over them.[3]

Judge Spero, in particular, was first appointed in 1999 and is well-known for finding amicable resolutions to civil disputes. When he presides, he promotes settlements and arbitration. But, the key thing to keep in mind is that phrase “with consent of all parties.”

Almost immediately, Quinn Emanuel filed their declination—they did not want the case to be heard by a magistrate judge. The case was reassigned to an Article III district judge, Judge Araceli Martinez-Olguin, who was appointed in March 2023. With only ~18 months of experience as a judge, there is considerably less history to review—in some ways, Judge Martinez-Olguin may be a bit of a wildcard.[4]

In requesting a district judge and moving away from Judge Spero in particular, one could assume that Quinn Emanuel and WP Engine are not interested in settling, not interested in arbitration. However, it’s entirely possible this is what they do in every case. Looking at the specifics of this case, I’d wager we’re in for a long fight.

“United States v. In the Matter of the Search of an Apple iPhone Seized During the Execution of a Search Warrant on a Black Lexus IS300, California License Plate 35KGD203” ↩︎

Cool cool cool. ↩︎

Judge Martinez-Olguin is currently presiding over Commure, Inc. v. Canopy Works, Inc., a trademark dispute in which Quinn Emanuel is representing the plaintiff, which mirrors the WP Engine complaint. However, the initial complaint was filed on April 30, 2024 (i.e. just ~6 months of history) and the details of the case are considerably different. ↩︎

Member discussion